Please note: this story was provided by the author and published as is.

I was his first born.

I still recall the words my father spoke as my lungs inflated with air and I gasped my first breath. “My child,” he said. “My little miracle.” His eyes welled with tears of pride. “Come…see. I have made a special home for you where you will be safe. It even has its own garden.” He held my naked form in cupped hands and carried me over to the countertop which ran around the perimeter of the room. And his eyes never left my face. Not once.

Father set me down upon a circular board lined with a bed of dried grass, and propped my spine against a small, crimson-leafed maple, sculpted from the real thing. Placing a glass dome over the top, he stepped back. “There,” he said, grinning from ear to ear. “Aren’t you something special? We’ll make many a sovereign, you and I.” The workshop was bitterly cold, and as he spoke his stagnant breath clouded the glass.

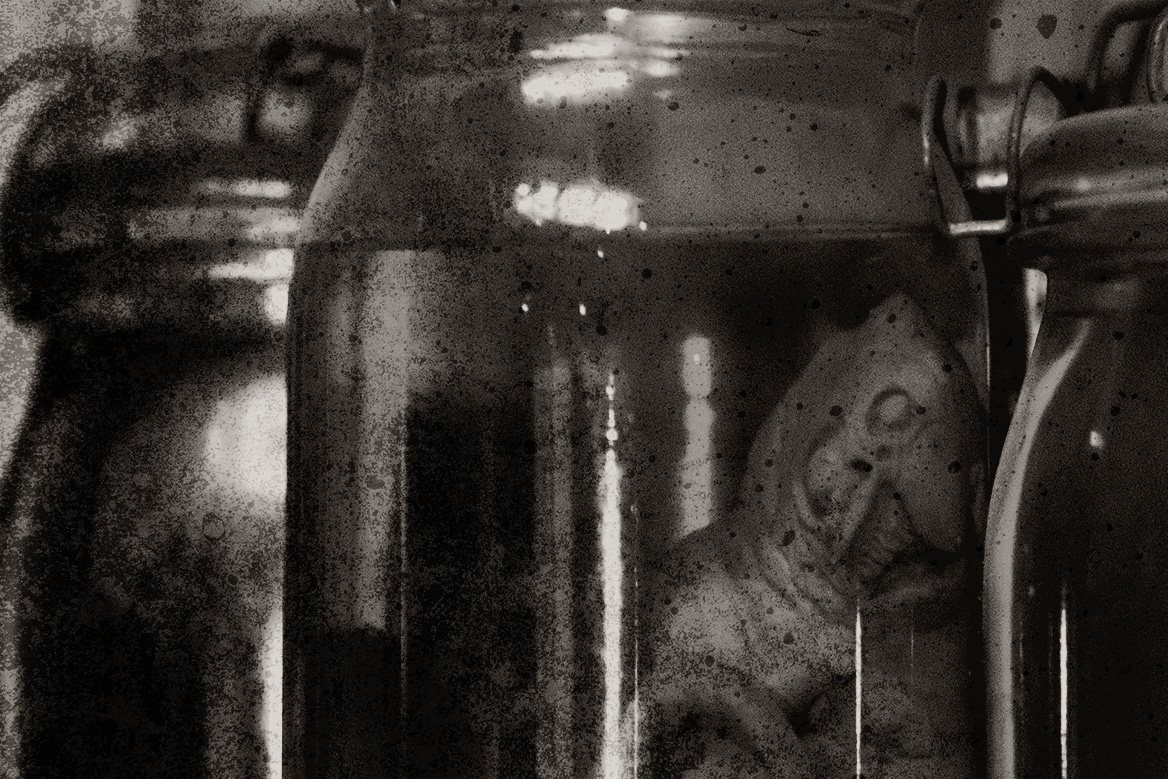

As the condensation cleared, I saw my reflection for the first time. There, grotesquely magnified by the curve of the dome, was the head of a tiny infant. Narrow eyes, puffy and expressionless, nestled in mottled skin, the colour of dried lavender. Gaping nostrils flared and narrowed to the rhythm of my breathing, whilst flaking lips, tinted blue, struck a horizontal line.

Father continued to watch as I took in the spectacle that was me. Of course, I did not yet think of him as Father. In fact I thought very little, for in those first minutes I was barely cognizant. And yet, with each lungful of air, awareness of my surroundings grew.

Around my throat I wore a necklace of cross stitches, sewn from the thread of horse hair and caked with dark, dried blood.

But my chest was magnificent! Arrow-shaped feathers, in shades of bronze and sepia, nestled amongst a background of pure white down. I later learned that Father had endowed me with the body of a tawny owl. He’d clipped its wings though. He would never allow me to fly. He had also chosen not to provide me with legs, unlike some of my siblings who came later.

For several minutes Father and I studied each other, unblinking. Beneath small, round spectacles, his pupils shone wide with excitement, and his scleras were interlaced with bloody tributaries. A toothless grin sat below a salt and pepper moustache which was yellowed with tobacco stains. Sprouting beneath a cap, an abundance of snowy white hair waved in all directions.

Eventually he spoke. “We must name you,” he said, in a voice cracked with emotion, “but I shall need to give the matter some consideration.”

Before he retired for the night, Father placed my bell jar on a high shelf so that I gained a bird’s eye view of the workshop.

To my right, in a glass specimen jar, floated the trunk and limbs of a new-born baby boy. Suspended in formaldehyde, the headless corpse was left floundering. It wasn’t until much later that I realized it once belonged to me. To my left, and in a similar jar, the large round eyes of a tawny owl stared in shock.

From this elevated position I took in my surroundings: a cluttered industrial room, with high beamed ceiling, brick walls, and bare floorboards. Wooden shelves were stacked with old books and all manner of bottles and jars, labelled in Latin. Around the perimeter of the room ran a narrow countertop littered with hand-written notes and diagrams, animal hides, and bones. I studied the implements on the workbench at the centre of the room, the one upon which I was born: bloody knives and scalpels, tweezers, needles and threads were strewn haphazardly—a murder scene in miniature. Or was it? For Father had brought forth new life from the carcasses of the dead.

Around the room, his most prized works of art were displayed in glass cases and domes: a red fox wore a hide of peacock feathers; a white mouse, carrying a tiny tea tray, stood on hind legs; a ginger kitten, with the wings of a dove, was suspended from wire as if in flight. I watched them closely for signs of life, though none so much as flexed a muscle.

I later learned they were his practice pieces. Only after Father had made his pact with the dark stranger was he granted the ability to breathe life into another.

On the second day Father woke me early, before the sun had risen. He appeared anxious, but once he was certain I had survived the night he calmed. As he removed the glass dome, I scrutinised his face without the distorted magnification of the concave glass. His frown of concern eased as he examined my neck wound.

“Knitting together just fine,” he said. “Your head must be able to follow the gaze of your audience. When these stitches heal, you will be able to rotate two hundred and seventy degrees through the neck without breaking blood vessels or tearing tendons. What a spectacle you’ll make!” His eyes glinted like jewels as he spoke.

The very next day, the travelling freak show came to town.

In preparation, Father carefully boxed and loaded his prize specimens into the back of a little wagon. Last but not least, I joined them. Father packed the space around my bell jar tight with straw, thus shrouding my vision. Having harnessed the horse, we set off. After a while, the rhythmic clip clop of the mare’s hooves lulled me to sleep.

Before long we reached the town square, and I heard Father whoa the horse. Having set up his display, Father gathered his fellow friends and gave them the spiel about how he had created a new freak of nature. “Are you ready to see?” he said, before whisking away a drape of red velvet which had thus far concealed me from prying eyes. As I blinked into sudden daylight, an audible gasp rose from the onlookers.

There in front of me stood a young woman, approximately half way through her third decade. Her wide mouth gaped open, displaying two enormous front teeth which were out of proportion to the rest of her face. Strangest of all was the top of her head, for its conical crown appeared to belong to a different person, someone much smaller or younger.

Looming over her, in stark contrast, stood a giant of a man, so tall his shoulders extinguished the sun, or so it seemed.

The girl with the conical head spoke, and despite my lack of experience, her words and tone were all wrong—mouse-like and nonsensical.

“Is it another of your taxidermy stunts?” a gruff female voice called from the rear of the crowd.

“Come, see for yourself,” Father replied. His expression was one of sheer joy as a rotund woman, scantily dressed in vivid red, jostled her way to the front. She bent down to get a closer look, and as she did so, oozing rolls of fat escaped her clothing. As I rotated my neck a half turn, the audience gasped as one.

“It’s a trick!” someone cried.

“Some kind of automaton,” shouted another.

But the fat lady knew what she had witnessed—the head of a new-born infant, upon the torso of an owl, had turned its face away from her. “Aren’t you kinda sweet?” she said, and the distorted image of her heavily made-up features reflected inside the glass surface of the bell jar. Her smile was wide, but I recognized the sadness in her eyes.

Moments later, the booming voice of the showman called everyone to order and I was whisked away until it was my turn to be leered at by a paying public. My heart raced as I awaited my destiny.

It has to be said, the showman did an excellent job of building up the crowd. His tone was majestic, imposing, and his lurid vocabulary and enticing phraseology whipped them into a frenzy. One by one, or in the case of the Siamese twins, two by two, the living exhibits were paraded before the insatiable audience. Hirsute ladies, a child with neither arms nor legs, and middle-age men, no taller than my display table, took turns at being ridiculed.

And it seemed I was the only living creature amongst them to be sickened by the spectacle. The only one who saw through the cracks, the grinning veneer.

And my tiny heart bled.

All too soon the spotlight shone on me. A thousand faces, or so it seemed, took turns to gaze into my house of glass. Each face magnified and distorted into a living nightmare. Each shriek of laughter, each cry of horror muffled by the glass, reminding me of the moment of my birth as the chloroform wore off. The memory of its sickly-sweet smell, accompanied by a profound sense of confusion, came flooding back until I thought I might vomit. But even if I had wanted to I would not have been able, for Father’s alchemy dictated precisely which movements were and were not possible.

Soon I was exhausted. The stitches in my neck pulled and my throat was parched with passion.

As to the secrets of his trickery? Of course, Father gave little away. Instead he soaked up the lurid attention like a beggar did cheap gin.

As evening fell, the crowd dwindled. Father collected five shiny shillings from the showman and we set off home.

Exhausted from all the attention, and desperate to be reacquainted with the relative peace of the workshop, I was rather disappointed when Father pulled up the wagon shortly after leaving the fair. Boxed and blinded by straw packaging, I saw nothing, though to some degree I was still able to hear.

Judging by the echo of the horse’s hooves, I imagined Father must have turned down some kind of narrow alleyway. He pulled the mare to a halt. Soon the sound of hobnail boots approached, followed by a short exchange between Father and another man who spoke in a hushed tone. The door of the wagon opened briefly, and a box of some sort was placed on the floor. The clink of coins announced an end to the illicit meeting.

The following morning, Father created my brother.

From my viewing platform on the shelf above his workbench, I watched with fascination as Father laboured, his aged hands as supple as a child’s and his eyesight as keen as a hawk. Unusual, I thought, for one so elderly, but later, having learned of his pact with the dark stranger, it no longer surprised me.

The sweet, pungent smell of turpentine and tanning oil permeated even through the miniscule amount of air space between my baseboard and glass dome.

And Father was in his element.

Not one for waste, he amputated the tiny feet from what remained of my carcass and attached them to the front legs of a headless hare, leaving its hind legs intact. The head of a badger, with its distinctive black and white stripes, replaced that of the hare. Finally, he reattached the hare’s long ears.

Glancing in my direction Father said, “Have no fear, little one. You shall be the only one capable of human thought and emotion, for it is you who received the human brain.” At the time, his words made little sense. It was much later, and after being subjected to the cruel scrutiny of humans, that I understood their true impact. And it was then I wished I had never been born.

Oh, cruel world! Why does mankind find it necessary to gawk and thrill at those who bear the mark of difference?

I would grow to envy my badger-brother’s lack of sentiment, as I would those who came later, though they too suffered the impediment of confinement.

I will never forget Father’s next act, for it was the first time I witnessed such alchemy.

As my brother lay prone upon the bench, Father took an intricately carved, spouted cup from a locked cupboard and breathed into it, long and deep. Inserting the spout between my brother’s dark lips, he tipped the cup backwards, at the same time reciting words in a foreign tongue. Within moments, my brother took his first breath and opened his eyes. Father cooed over him for a short while, before placing him inside a glass dome not dissimilar to my own. Of course, the same sorcery had been cast on me, though I had no recollection of it.

It dawned on me later, after Father had created three more siblings, that through his alchemy not only did he create life, but he also controlled its limits. My brother, fashioned from badger and hare, was able to move only his ears. Hearing was his most acute sense, so when spectators viewed him within the dome, his ears would twitch and stand erect at the slightest change in sound, resulting in shrieks of laughter.

One of my sisters received the nose of a black bear, set within the face of a fox. She therefore inherited an acute olfactory system, and thus was constantly hungry, though rarely fed. Which brings me to the matter of sister, for the felonious exchange that had occurred between Father and the man in the alleyway was the trading of a human corpse for a coin. Stillborn, though nonetheless illegally purchased, I began to understand that Father was procuring dead infants so that he might experiment with what he called, his marvellous children.

The carcasses of birds, reptiles, and mammals he either sourced himself or through his acquaintance with a local poacher.

As Father grew more confident in his work, his skills became more adept, until he was able to adorn his creations with minutiae detail, such as attaching the curled eyelashes of a cow to the head of a grass snake, and gifting it the power to flutter its wares at gentlemen observers.

On one occasion, he encrusted the chest of a falcon with live snails which peeped from their coiled shells in tune to Father’s harmonica.

As his living curios became more and more famous, Father grew wealthier, and thus was able to afford more exotic birds and animals from far-off shores.

He stuck to his word, though. Never again did he grant a creature the brain of a human.

Of course by now my own trick of being able to follow the gaze of admirers had worn off in comparison to the new delights Father had up his sleeve. Truth be told, he grew bored of me, sometimes forgetting I had not been fed, or that my dome had not been cleaned for several days, until the acrid stink of my own excrement burned my nostrils.

And he never did name me.

It was around the same time as the procurement of the tiger carcass that things began to turn especially grim. By then Father was intoxicated by his success, thrilled with each new addition to what he termed, the family. He’d grown affluent, infamous, and had no need to work any longer. But we had become his fix, his drug of choice, and he was neither willing nor able to relinquish the reins on his power over mortality.

Of course, the unsuspecting population assumed his works of art to be some kind of clever trickery or puppetry of sorts. Rumours whispered behind closed doors, eyebrows were raised and elbows prodded, though nothing came of it. Father was even questioned by the peelers, though he managed to charm them with his guile.

Then, one day, shortly after midsummer’s eve, Father brought home a live one.

A cry of hunger reverberated around the workshop as he lifted its naked form from the swaddling. It lay on the cold workbench, angry and alert, legs kicking and fists crammed into its mouth. I watched helplessly from my perch, heart racing, as he selected the sharpest scalpel from a leather roll.

Licking his lips, he made the first incision, and I squeezed my eyes shut tight, wishing I had hands to cover my ears against the unholy scream.

A sudden blinding light pierced my lids, and the room was filled with the roar of one incensed. The flash of light abated, and I peered into the gloom towards the only Father I had ever known. And I smelled his fear.

Drained of life blood, the infant’s cry ceased. Father held the scalpel aloft, whilst blood dripped onto the abdomen of the tiny corpse. Father’s face froze in shock at the sight of the tall, dark being who towered over him. I saw in Father a moment of recognition and understood this was not the first time the two had met.

The stranger spoke, and in doing so a conflagration of flames spewed from his mouth, singeing Father’s face and causing him to cry out in pain. “This was not part of the bargain,” the stranger said, gesturing towards the prone body of the infant. “You have grown greedy and lustful and hence you shall be punished.”

Father did not reply, for his pain was too intense.

“We made a pact which gave you power to reanimate the deceased, not to take the life of the innocent.

And with that, he wrapped a cape of burning wings around my Father, consuming him in flames, until he was no more than dust.

*

The dark stranger visits each of my siblings in turn, contemplating the complexity of their makeup. His frown is stern, flames of anger which put paid to Father’s life extinguished. As he reaches me his expression changes to one of empathy, for reflected in each other’s eyes we recognize something of ourselves. Both of us bear the burden of difference.

What will become of me and my siblings I cannot say. All I wish is for this cruel carnival to end, and that one day the people of this world will embrace difference with open arms instead of jibes and ridicule.