Please note: this story was provided by the author and published as is.

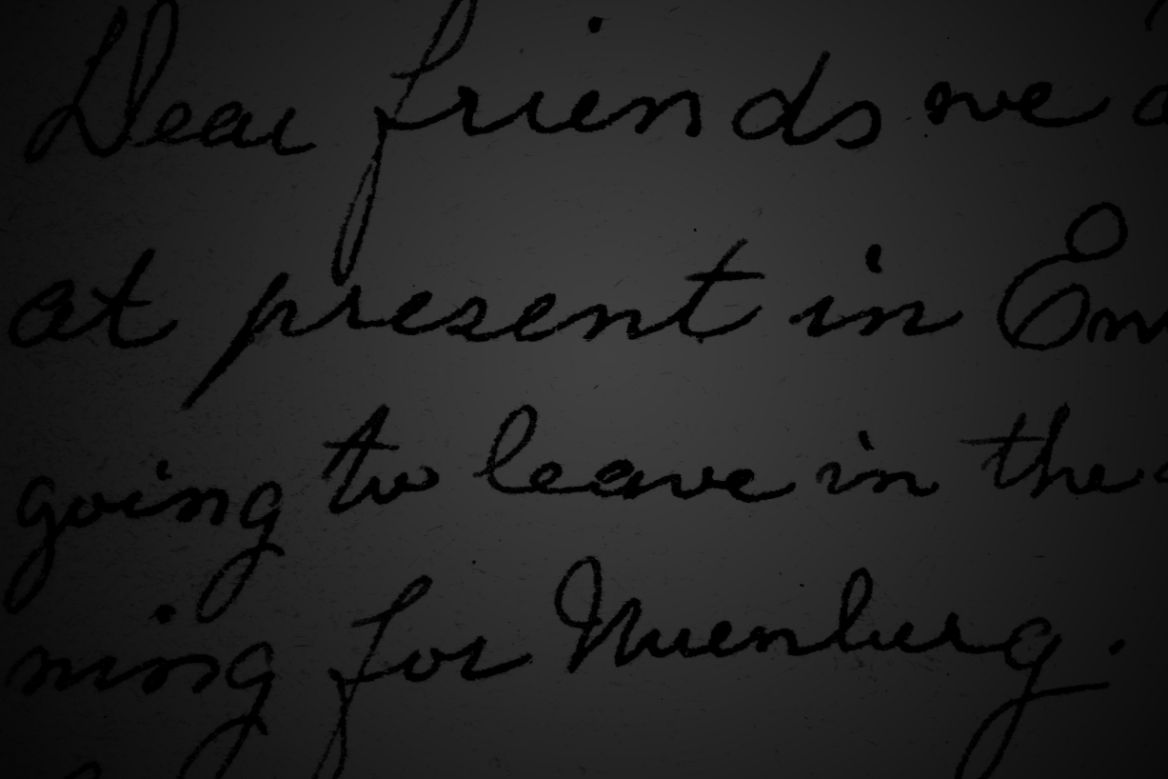

Dear son,

You cannot come.

I know the last time we talked over the phone, you discussed coming back to spend time with me before I “went away,” as you so awkwardly placed it. You were right when you said that our relationship hasn’t been the same since your own boy was hatched into this world.

You couldn’t have realized it, but all I can see when holding him is the face of Butch Powers, my childhood neighbor who infected our lives forever. You cannot come, and I know the only way is for you to understand just why that is. So here it is.

Oh, God, here it is.

****

Butch Powers was our neighbor in the year of 1968. Back in those days, the word

“neighbor” applied to the two houses you could make out on the horizon if you stood on the front porch and squinted your eyes just right. We lived in farm country, and capering all around us was the unwavering flicker of wheat and corn. A single, dirt-tracked road stretched out east and west like the world’s oldest snake skin; during particularly hot days, dirt spewed up in heavy clouds, and you could see the arrival of a guest five minutes before they coughed their engine onto your plot, black diesel fuel fumigating the air as they throttled down into first gear.

As a sixteen year old boy, I had spent my summers and winters working under my father. We tended a plot of land that would be laughed at in comparison to today’s McMassive lands, but we managed what we could. Often, I took up odd jobs for other farmers helping pick rocks in the fields come March, or baling hay in barns festered with rickety boards and damp smells. The hay nettles scratched at your arms like poking fingers that left dark red rashes.

It was clear from a young age that the life as a farmer might not be my final rest stop (usually, you would see me perched under a tree in the late afternoon, a book propped in one hand and one of Mom’s blackberry muffins in the other); it wasn’t that the work was necessarily grueling (though it certainly could be), and it wasn’t that I had grandiose thoughts of being an astronaut like my childhood friend John Kolbowski, who was apt to be seen gazing at the sky with spittle running from his lip.

My body simply rejected farm life much like a fish refuses the toxic air of humanity.

During days trooped in the corner of barns or haylofts, my nose would gush white phlegm that rolled from my nostrils in gelatinous globs. My face would puff bright red, and my eyes looked like I had gotten into Jimmy O’Neal’s special herbal garden he thought no one knew grew in the middle of his corn field. It was common practice for me to go through multiple bandanas in a day, blowing snot and sweat in great big honks!

Even then, I understood dedicating myself to farming would award me a life full of certainties: certain that I would flounder in my own phlegm; certain that the chaff of hay would flay open my skin time and time again, turning my arms into torches that smouldered like hot ash. It’s been fifty years since I last touched a hay bale, fifty long years , but even now I can feel that certainty of never leaving those endless fields snake itself inside me.

So, when Mr. Powers requested that I come work for him that summer of ‘68, I was over the moon with relief. Who cared if he was riddled with some disease he would rather not speak more on? What sixteen year old boy thinks more about the way Mr. Powers had looked when making his request on our driveway–a long black trench coat in the early June sun, his face a white shadow mostly concealed by a dusty bowler hat. It was my father who had looked at me and asked what I had thought. I had stuck out my hand to Mr. Powers as if that was all there was needed said on the matter. We clasped hands, the young shaking old, and then he pulled away. Who cared if he left dregs of shed skin on my hand? At least I was out of the clutches of farm work.

Cooking meals, cleaning his house, tending to his bed pan were all so much more alluring than the burning stints spent out working with the other farm hands. The best part was Mr. Powers needed me every day, from sunup to sundown, until the night nurse came. During the dry days of July and August, I could practically see the harsh rays of summer whipping in the air outside.

During those first two months of summer, I mostly just did Mr. Powers’ housework. As a chef, my skills graduated from stiff scrambled eggs and burnt toast, to omelettes made fresh from the vegetable garden. I swept the floors, wiped down the windowsills, and collected the daily paper from his mailbox that sat crooked on the edge of his driveway. I didn’t see Mr. Powers as often as you might think; his daily meals I served to him in his bed, and he would quickly usher me from his room. But I cared for him, you see?

Once, during a wicked July thunderstorm that caused the roof to sprout leaks of rain water, I came into his room unannounced with a new bed sheet and some buckets. When I walked in, his linens had been thrown across his ankles. Running down his chest in criss-crossing X’s were blue veins as thick as tubes. I thought I could see them pulsating. It reminded me of the body of a serpent slithering across the midriff of Mr. Powers in shades of aqua. Through his skeletal chest, I could see the throb of his heart go whack, whack, whack, until he had slithered down and retrieved the blanket.

“Ohmygosh,” I had spit out all at once. “Mr. Powers, I didn’t mean to walk in on you like this, I thou…”

“It is not a problem, Jefferey,” Mr. Powers cut me off. His face wore a strange expression. Standing there that day, I had mistaken my unease over the fact of his very evident sickness. Just what in the hell was he sick with anyway? All these years later, I realize my fear had evolved from those eyes of his, staring at me with hypnotic obsession.

Hunger eyes, I remember thinking.

“You are an inquiring boy, I am sure,” he had said. “Your, ah, intentions must be put on hold, though. I am dreadfully tired.” His words scuttled from his mouth in a slow crawl, those predator eyes of his holding me in their gaze.

He bade me goodbye that day with fingers that looked like spider strands.

How do you know when it’s time for another to die? I hope you see the signs, son, as I ignored them that day, August 4th, 1968. They’re death signs, you know.

That day in August was overcast and broody. It was the type of air you feel right before a tornado slams itself down and starts dancing around. That morning, I had woken up early and made my mother and father homemade french toast, crisp bacon, and a crock of fresh strawberry sauce. Before slipping out the door for Mr. Powers’ place, I left a note: Breakfast is on the table, chores are run for the morning. Be back later tonight. Love, Jeffrey. There was a red splotch on the paper where strawberry had dripped.

Often the teen years are heaped with ugly memories as the growing adult attempts to jump from the nest, parents desperately clipping at their wings in a last way to cling to those longful days of youth. I’m glad I left that note. For whatever horror I witnessed that day, I am happy to at least have that small spark of light.

The morning air that day was unusually cool and stiff; I remember wishing I had grabbed my rain coat before leaving. Mr. Powers lived under a quarter mile from us down the road, his driveway marked by the Leaning Mailbox of Powers. I quickly hurried down the gravel to his house.

On any given day, you would normally be greeted by a garden of sunflowers Mr. Powers kept on the west side of the place. Though by no means a grove of flowers, the little nest of yellow and black heads bobbing to their silent siren calls was usually a tranquil experience.

Rounding the bend of his driveway, I at first did not notice what should have struck me as queer. My mind had been focused on the quality of the air

(Was there going to be a tornado today? Would Dad and Mom be okay getting into our cellar? How would I get Mr. Powers down into his cellar?)

That the sight of the dead flowers nearly passed me by. They were sprawled on the earth like a legion of fallen soldiers. As I moved closer, I saw that their stalks had a chewed and frayed look to them, as if some predator of the night had a taste for the flesh of flowers. Holes punctuated the dirt.

There wasn’t a wind, I swear to you that air was stiff as frozen nails, but a decapitated head of a sunflower rolled toward where I stood. Most of its yellow leaves had curled into husks that resembled knuckles. It shook and buzzed, shaking slightly as if stuffed full of a swarm of bees. The black seed of its center drooped open like a flap of skin, revealing an orange eye swimming with insects. It blinked away bits of dirt and its gaze peered up at me. It made a kind of mewling cry of joy and hunger.

Horrified, I backed away. My hand groped blindly for the door knob, my eyes never leaving the sunflower head (eye that’s an eye and it’s looking right at me) before I realized my butt had slammed itself against the door. Desperately, I tugged at the handle.

Locked.

Sluggishly, the eye began to roll towards where I stood. It left a trail of orange slime where its black bat body touched. I could feel fear punching at my chest with heavyweight fighter fists, and for the first time that day I thought about death as something real and tangible.

This was 1968 remember, and so that movie franchise about the aliens that suck onto your face hadn’t come into existence yet. But as that eye continued its gelatinous roll towards me, I had a vision of it reaching out with razor-like tentacles, pulling my face towards it. I could see myself getting closer and closer to its dead gaze, seeing the wings of flies buzz around its pupil, could feel the wet suck of its jaw buzzing at my lips…

I fell through the doorway, finally realizing I needed to push the door open. My ass hit the kitchen linoleum with a thunk! The reflection of a terrified kid swam in the eyes’ large gaze as I kicked closed the door. From behind it came the angry chirp of an animal cheated from its feeding time.

Look at me, Ma, no hands! shot wildly through my head.

It was then that I realized I was laughing in short, shallow breaths. I had torn a hole in one of the knees of my work pants, and my hands were rashed from sliding back onto them, but that was okay. Tears dropped onto my palms as I inspected them. That was okay, too.

I was alive.

Those next moments defined the remainder of my life. I had options, you see, and I chose the wrong path. I wish I had fled. Just flung open a window, vaulted out like Carl Lewis from the blocks, and have been gone. See ya, baby, but I’ve got to jive. What a fool I was, son, for I chose the path of love, protection, courage. All foolish qualities, I have come to realize, and yet we exhibit them all the time. Learn from my mistake, son, and leave everyone you have loved as I failed to once do.

I had picked myself off of the kitchen floor using the counter as leverage. Clean mugs hung from the wall on screws, the handles chipped from many years of use. I took one of them off their peg for water. I drank an entire mug full in three desperate gulps, leaned forward to fill it again, and looked above the sink through the window.

The garden of dead sunflower heads had erupted into a crush of rolling eyeballs, blinking stupidly with dirt in the gray morning. I saw a chickadee bird land in the grass a few feet from the field. With a flash, a pair of fleshy tentacles reached out and jerked the bird from the earth. The eye flattened itself on top of the bird. I realized it was digesting the poor creature whole. Bits of feather were rocketed into the air in shades of brown and blood red. I want to be an astronaut, the voice of my friend John Kolbowski hee-hawed in my head.

Showers of half-digested french toast flung into the sink on my side of the window. With shaking hands, I wiped saliva and vomit from my chin. I did not want to look outside anymore.

Mr. Powers’ room was just down the hall from the kitchen. As customary, his door was kept closed. For the second time that summer, I entered the room without knocking, sealing my fate as easily as a fly caught in the web of a spider.

Everything was all wrong, I sensed that right away. There was a too dark quality to the room even though the window shades were thrown wide open. Think about when you hang a pillowcase or towel over a lampshade; the light takes on a dark underglow that makes it feel like the shadows have their own heartbeats. That was what the light was like in his room, but it also wasn’t like that at all. I’ve spent my entire lifetime attempting to find the switch that throws off those inhuman lights forever.

I still cannot find the right words to turn them off.

It was the light of the room, but it was also the smell that struck me when I entered. Here lies the animal’s den, I thought. There was the smell of rank food that clung to the air in an onion-aftertaste. There was the smell of dying carcass left out to rot, smouldering and blackned, under a beating sun. Underneath both of those smells was an odor much fouler, something pungent and old, like an open coffin after years of being sealed shut.

Mr. Powers lay on his tomb of a bed with the sheets puddled on the floor in strips of white and red. His entire body was the color of sour milk, a curdy kind of white. The face he had worn one last time before being ripped apart was of total serenity.

Where his chest once was (all criss-crossed with those awful thick tubes that had crept into my dreams that summer) there now was a hole the size of a basketball. Bits of white and reddish goo seeped out in rivlets that steamed in the strange light. Something was writhing in the cavity of its dark hole, and I moved closer to look. I moved closer to look, damn me.

At first, I didn’t understand what I was looking at. A small, orange object was writhing in a mass of intestines of whose owner I didn’t want to consider. It’s a honeycomb, I thought. The object was jagged and warped like a piece of paper crumpled into a ball. Infant-like cracks shattered its shell in insect-like sluggishness. The thing pulsed in and out, its warbled body making sloshing noises as it contracted.

A drop of rain water fell down from the ceiling and struck my head.

Close up to Mr. Powers, I realized what I had mistaken to be his intestines were actually small, tubular worms covered crimson red. They were thrashing their infantile bodies against one another creating a horrible slurping sound. Their bodies were silky looking and thick, some up to six inches in diameter. A bundle of them tumbled from the chest cavity onto the lap of the dead man in front of me. Eyes were not required for their squirming, but I watched as one opened up its front, revealing a cavern of sharp little teeth like buzzsaws. Clots of worms slithered up and around the orange honeycomb in sickening clumps.

That’s why it looks like it’s breathing, I thought then. It’s just those disgusting wo- The honeycomb split into a nest of cracks that splintered into nugget-sized holes.

Something inside was moving; something thick and muscular was slithering inside of the shell.

Momma’s awake. The thought acted like a gunshot that broke me from my trance.

Too late.

The honeycomb exploded in a spray of gooey bits that I later found in my hair. A gigantic snake creature uncoiled its body in layers of maroon, purple, and nightmare black. It had the thick body of a six feet wide sewer pipe, and, like its babies, it didn’t have any eyes. But, as fear held me prisoner, Mother Snake cracked wide her front to reveal a nest of hundreds of fangs, each like tiny daggers in the strange light.

“Holy shi-” wheezed out of me. The front of my pants began to darken as my bladder let go of control. And, for the first time that day, I did something smart–I ran.

The door was only seven steps from Mr. Powers’ bedside; hadn’t I counted those steps for the last two months? I felt trapped in a dream where no matter how hard you churn your legs and make the dirt dance at your heel, you somehow don’t move at all. My brain kept yammering run, run, run ! Behind me, I could hear the slap of that giant creature crashing down onto the hardwood floor. I was a step away from reaching for the door, just another piston of the leg, when I slipped on a pool of water from the leaking ceiling.

Where’s the bucket when you need it, I thought as I careened toward the floor.

I slipped falling forward, thus saving my life that day. Had I slipped backward, and so head first, into the slithering masses of those alien creatures…

I landed with my palms shooting across the floorboards. There was maybe one second for me to think I can still get out of here before my left ankle was wrapped in a burning flame. I snapped my head back to see hundreds of worms waterfalling from the bed in pursuit of fresh food. Momma Snake had her buzzsaw head buried on the bone of my ankle. I could feel her razor teeth sink into my flesh with delicious ease. Her great slithering body slapped back and forth across the floor, creating gouges in the wood. Blood sprayed from my skin in a frothy jet.

Poison, poison!, my mind wailed.

Instinctively, I reached down and seized her swollen body with both hands. Its reptilian scales were oddly warm and stiff. I yanked with all of my strength but she would not tear free. Her bite intensified in pain; those needle teeth dug deeper into my skin. I could feel them clawing at my tendons in sickening snaps. One of the baby worms suckled its way onto my shoulder, latching onto the side of my neck with an alarming strength. Warm fluid ran down the side of my arm.

She’s too heavy to throw off, I thought.

What gave me the last bit of strength was the image of all those creatures swarming my face. I could see tides and tides of them burrowing like moles underground.

With all my might, I yanked Mother Snake off my ankle and threw her back. Scrambling to my feet, I lurched for the door, nearly falling as I tried putting weight onto my ankle. The door gave a screech of its hinges before I was in the hallway again, quickly slamming it behind me.

It took me a second to recognize what the sucking sound was, until I realized that one of the babies was still dangling from my shoulder. Its body had ballooned to twice its size.

When it splattered against the wall, a horrible spray of red and yellow gushed onto a family portrait of the Powers family.

****

There you have it, son. The reason you cannot come.

Do you not see it?

Let me tell you one last quick story that you thought you already knew:

You were three, and your mother and I had set you up outside in a portable playpen one evening some late July. I had the grill licking away at chicken legs; your mother was hanging clothes from the line. A great big yellow jacket landed on your favorite stuffed dinosaur, Rexy. You swatted at the wasp, and in the process, found out that you were deathly allergic to bees.

All sounds like last year’s record, yes?

Here’s what you don’t know; here’s what no one has ever heard until now.

As your mother drove our station wagon at a reckless pace to the hospital, I sat with you in the backseat. Your face had swollen to the size of a watermelon. Gushes of air were being squeezed through your lungs like the sound helium makes as it leaks from the tank.

“You are going to be FINE,” I kept yelling over and over again. My chant took on its own talismanic rhythm. I kept shouting it even as your breaths began to slacken, then stopped.

Your mother screamed the car in front of the emergency room doors. Throwing open her door, she did not see the small tubular worm that sprouted from your lips. It wiggled its plump body in a horrific shake and fell onto the seat of the car. Your face was the same curdy white of a man I had known long ago. I picked up the worm and threw it out the window, holding in a silent scream all these years that can no longer be held in.

I am afraid because last week I noticed a skeletal figure staring back at me in the bathroom mirror. This figure had blue tubes racing across his chest that slithered like snakes in a sunflower field.

I am afraid because I know I will wake up to find myself swarmed in that alien light for the second and final time. Some nights I can almost see it seeping through the walls with alien fingers.

Mostly, I am afraid of what I have infected us with. I am afraid of what lies nested inside of me, almost ready to hatch. What lies in me, my son, lies in you. It lies in your own son, I have no doubt.

And, if we were all present in that alien light, what do you think would happen?

Would Momma call out to babies? You cannot come, son.

You cannot come.

With bitter love,

Dad